1. INTRODUCCIÓN

Napoleon’s conquest of Italy led to the birth of various republics that were satellite states of the French Republic. These states merged first into the Cisalpine Republic and then into the Italian Republic, which was established on 26 January 1802 with Milan as its capital and Napoleon Bonaparte himself as its President. A few years later, France was proclaimed an empire and consequently, in 1805, the Italian Republic became the Kingdom of Italy, although its territory was limited to north-eastern Italy and its borders remained unchanged to those of the previous Italian Republic. However, in the following years, new territories were acquired that extended the dominions of the Kingdom (1).

During the Italian Republic new reforms were enacted, several of which affected public education and universities. The Public Education Law of 4 September 1802 (2) was written with the aim of standardising public education in the territories of the Republic. Article 48 of this law stipulated that the exercise of the most “interesting professions” was to be entrusted to persons of known suitability and that therefore a degree and a subsequent approval were necessary for the exercise of six different classes of professions. Since these six classes included the pharmacist profession, the university pharmacy programmes at the two national universities of the republic at the time – Pavia and Bologna – were restructured and reorganized. The University of Padua was also included a few years later, during the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy. With the 1803 Study and Discipline Plans for National Universities (3), faculties were created that grouped the various professorships according to the type of teaching. Three faculties were set up: the Physico-Mathematical Faculty, the Medical Faculty and the Legal Faculty.

The pharmacy degree programme was part of the Medical Faculty and had a duration of three years. The first year included subjects that were compulsory for the other degree courses as well and which were not strictly related to the scientific domain of pharmaceutical studies. As a matter of fact, first-year-subjects were Analysis of Ideas, or, in other words, a logic course, and Italian and Latin Rhetoric. The second and third years, on the other hand, included subjects that were specific to the Pharmacy degree course: Botany, Materia Medica, Pharmaceutical Chemistry and General Chemistry.

Obtaining the academic degree did not mean being able to exercise the profession immediately: it was also mandatory to carry out five years of apprenticeship, which the aspiring pharmacist often began before obtaining the degree certificate. Once the academic diploma was obtained and the five-year practice completed, the candidate had to take a new exam in order to obtain the authorisation to practise as a pharmacist and thus be allowed both to work in a pharmacy and manage one.

In this research I present, for the first time, the proclamation, oath and licence formulas of the Italian pharmacists during the Napoleonic period. These documents were found in the old file catalogue of the University of Bologna in the Bologna State Archive. The oath, in particular, used to be signed and solemnly read before a commission after the candidates had sat both the academic and the qualification exams.

As far as pharmacy is concerned, this is the first time there is trace of a specific oath for “farmacisti” (pharmacists). As a matter of fact, before the reforms of 1802 and 1803, those who practised the profession of preparing and selling medicines were identified by the term “speziale” (apothecary), “maestro speziale” (master apothecary), “speziale medicinalista” (medicinal apothecary) or similar titles. In the past, apothecaries too, just like physicians, used to take an oath after they had been approved by their respective city guild. Admission was of course regulated and the criteria set out in the guild’s statutes had to be met, meaning examinations were necessary. For example, very old proof of this comes from the statutes of the “Arte dei Medici e Speziali” (Guild of physicians and apothecaries) of Florence in which it is reported that, in the 14th century, Florentine apothecaries took an oath when they were admitted to the guild (4). It should be pointed out that the institution of the new Pharmacy course did not represent a clear watershed in the use, in texts and laws of the Napoleonic period, of the nouns apothecary and pharmacist, or where these professionals exercised their activity: apothecaries and pharmacies. When obtaining a Licentiate in Pharmacy at the University became compulsory, over the following decades, the term apothecary was gradually replaced by that of pharmacist. The word “pharmacist” identified a person who worked in their workshop with in-depth knowledge of General Chemistry, Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Botany and Materia Medica.

2. THE PHARMACISTS’ OATH UPON OBTAINING THEIR ACADEMIC DEGREE

When students enrolled in a pharmacy university programme, they were required to attend classes and take exams. At that time there were two main exams: for the pharmacy course, the first one was held at the end of the second year and it conferred a Bachelor’s degree; the second one, the final exam, was to be sat at the end of the third year and it conferred a Licentiate in Pharmacy. When students passed this latter exam, they attended a solemn ceremony (5) in the Aula Magna of the university and received their diploma in pharmacy.

On the Thursday following the final examination, the Commission summoned to the Aula Magna of the university the students who had passed the examination and were to be awarded the academic degree. After the students and the Commission had assembled in the aula, the Rector of the University and the Chancellor entered the room. At this point, the University Chancellor read aloud each student’s examination papers and their corresponding approval.

After this, the Chancellor declared the candidates qualified to be awarded the Licentiate in Pharmacy, and an assistant gave each of them their diploma. Then, one of the new graduates had to publicly thank the faculty on behalf of all the graduating students and declare their common desire to fulfil their duties as pharmacists. All the students read and signed an oath in which they solemnly declared to carry out the pharmacist profession with dignity, care and in the service of the Republic.

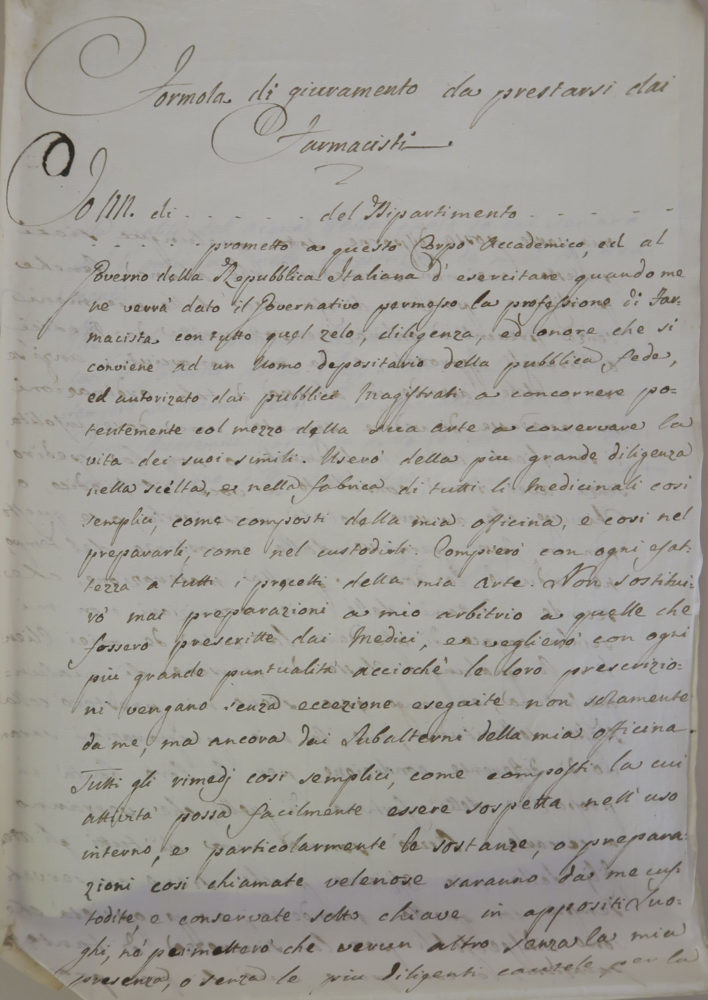

Below is the first oath that was proclaimed by the pharmacy graduate students at the University of Bologna (6):

Form of oath to be taken by pharmacists

I, [Name Surname] of [Town name] of the Department [Department name], promise to this Academic

Body and to the Government of the

Italian Republic to exercise, when granted governmental permission, the profession of Pharmacist,

with all the zeal, diligence and honour that is appropriate for a person who is a depositary of the

public faith and authorised by the public magistrates to preserve the lives of their fellows.

I will use the greatest diligence in the selection and manufacture of all the medicines, both simple

and compound, in my workshop, and in both their preparation and preservation. I will carry out

with all exactness all the precepts of my art.

I will never substitute the preparations prescribed by physicians at my own discretion, I will verify

with the greatest punctuality that their prescriptions are carried out without exception not only by

me, but also by the subordinates of my workshop.

All remedies, whether they are simple or compound, the use of which can easily be suspected in

internal use, and particularly those so called poisonous substances or preparations, will be kept by

me, and preserved under lock and key in special places. I will not allow anyone else without my

presence, or without the most diligent precautions on my part, to dispose of them under any protest:

nor will I allow even the smallest portion of them to leave my hands without a prior order signed by

physicians or surgeons approved and known to me: if, by any chance, in any of these orders, I

should happen to see an unusual dose of such active medicines marked, I shall not send it without

first having consulted orally the physician or surgeon who could have prescribed it, or if this is not

permitted to me by the circumstances of the time, I shall reduce the dose to such moderation that,

according to the dictates of my knowledge, it does not seem to me capable of offending the life of my customers.

Whatever class of people, of whatever fortune and rank they may be, I will serve them with the same

solicitude, and my preparations will not be of different condition in terms of their goodness in

proportion to the fortune of those who come to seek them.

I will take great care of all the utensils of my workshop so that they will always be kept with that

cleanliness and properties that are essential for the safety of so many preparations, and likewise I

will have the greatest attention to the quality of the water, which I will regularly use in the

composition of my medicines.

I promise to faithfully abide by these declarations, so that the Government of the Italian Republic may always honour me with its benevolence, and this Academic Body may in all circumstances recognise me as worthy of its illustrious approval.

It should be highlighted that the oath that was found (Figure 1) was specific to the pharmacist profession. This solemn promise emphasised all the qualities that good pharmacists had to have, namely that they had to be at the service of the State and the public health. As the oath states, pharmacists had to exercise their profession with zeal, diligence and honour, as the Government placed its trust in them to “preserve the lives of their fellows”.

Figure 1: The first oath that pharmacists took when they obtained their Academic Degree in Pharmacy (1804). Bologna State Archive (ASB), Studio, n. 530.

From a certain point of view, we can say that this oath already offers a preview of the rules of good preparation which modern pharmacists must adhere to when preparing formulas in the pharmacy laboratory. This preview can firstly be found in the fact that the preparations always had to be carried out perfectly in accordance with the recipe and had to be stored with due care. Secondly, they could not be arbitrarily altered, the laboratory tools had to be kept perfectly clean and the water quality had to be checked (at that time it was not a granted fact that the water quality was good). In the oath, the word safety, which is used in reference to preparations, stands out. As a matter of fact, when pharmacists prepare a medicine, they are responsible for the livelihood of the sick: if the medicine is not prepared in compliance with the physician’s instructions, not only could it be ineffective but it could also harm the assisted person.

The use of the word “customer” is also worth mentioning. This word, together with the word “sick”, was also used in the oath that physicians of the University of Bologna took during their graduation ceremony. The word “patient”, on the other hand, which was already in use at the time, does not appear in the latter. This article shall not delve into a philological analysis of the topic, yet an in-depth study of these words in their historical context and especially in the oaths of the healthcare professionals of the time would certainly be very interesting.

Pharmacists had to know very well how to carefully prepare and store both simple and compound medicines in their pharmacies, and their preparations always had to be perfect, even when these were prepared by their assistants.

A large part of the oath is also dedicated to the poisons that pharmacists used to keep in their pharmacies for medicinal preparations. The concept of poison is embedded in the very etymology of the word medicine, in Italian “farmaco”, from the Greek word “φάρμακον”: “farmaco” is that substance which, on the one hand, is a medicine and can cure but, on the other hand, is a poison and can kill. In their oath, pharmacists used to promise that they would keep poisonous substances under lock and key and that these substances could only be handled by them or in their presence. It appears clear that lawmakers paid great attention to the use of these active substances, which could be used both in an accidental and in a deliberate criminal way to harm people.

In this regard, it was reported that pharmacists had to comply with prescriptions intelligently. In the event that unusual doses of substances dangerous to the health were prescribed, pharmacists were to contact the physician or surgeon and ask for clarification. If contacting the prescriber was not possible, pharmacists could dispense the medicine in its minimum effective dose: with that “moderation that, according to the dictates of my knowledge, it does not seem to me capable of offending the life of my customers”. This point emphasises that pharmacists were not to be mere executors or manipulators of drugs. In the preparation of medicines, pharmacists used their scientific knowledge – obtained from their university studies and experience – to ensure that what they prepared, if used correctly, was not dangerous to the patient. It is equally important to emphasise the relationship with the other health professionals, in particular physicians and surgeons, with whom pharmacists had to deal with if doubts arose regarding their preparations. This aspect of health professionals consulting with one another also emerged. Evidently, it was an important lesson that was intended to be passed on to the new health professionals of the Republic.

The equality concept, dear to the French Revolution, is also present in the pharmacist’s oath. No difference was to be made between the wealthy and the poor in the preparation of a medicine and therefore the preparations were not to be “of different condition in terms of their goodness in proportion to the fortune of those who come to seek them”. Wealth and social status could not be a discriminating factor in the preparation of a medicine: whether a person was rich or poor, they were entitled to the same quality of medicine, without distinction of any kind.

This principle of equality can be found in a more developed version even in the oath that Italian pharmacists have to make today (7). As a matter of fact, today pharmacists swear to assist all those who call upon their professional services “with attention and dedication, without any distinction of race, religion, nationality, social condition or political ideology and with the greatest respect for their dignity”.

3. THE PHARMACISTS’ OATH UPON OBTAINING THEIR QUALIFICATION

As we have seen, in consequence of the reforms of 1802 and 1803, pharmacists had to obtain a further qualification after graduating. The law required that a special commission assess the pharmacists’ practical skills and therefore candidates were asked to pass an examination before obtaining the license that would enable them to freely practice their profession.

In 1805-1806, the body responsible for issuing such licences was the Ufficio Centrale Medico, Chirurgico, Farmaceutico (Central Medical, Surgical and Pharmaceutical Office), often referred to simply as the Ufficio Medico Centrale (Central Medical Office).

Before the Office was established in 1805, the Bologna Health Departmental Commission and the University of Bologna used to compete for the right to qualify health professionals. Paragraph 13 of article 9 of the aforementioned Study and Discipline Plans for National Universities of 1803 stipulated that, for professions requiring a licence besides a university degree – including the pharmacist profession – a further examination was necessary. The conflict between the two institutions arose from the fact that paragraph 13 did not state which body had to hold the examination. Instead, it simply referred back to the examination’s rules. This gave rise to a dispute between the Health Departmental Commission and the University of Bologna. The disagreement was eventually solved (8) in a meeting between the two parties, as evidenced by a letter from the Rector of the University of Bologna to the Prefect of Bologna dated 10 January 1804 (9).

The creation of the Central Medical Office made it possible to have a special body in charge of judging the suitability of aspiring professionals in the various branches of the healthcare field. The evaluation was regulated by specific rules for every branch. Initially, the Office was only based in Pavia, but, later, when the University of Bologna was recognized as equal to that of Pavia, a Medical, Surgical and Pharmaceutical Office was also founded in Bologna. This happened in 1805 (10). The Office remained open for a short time, as the Royal Decree of 5 September 1806 of the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy ordered the closure of the Central Medical Offices and decreed the creation of the Medical Police Offices (11) (Direzioni di Polizia Medica).

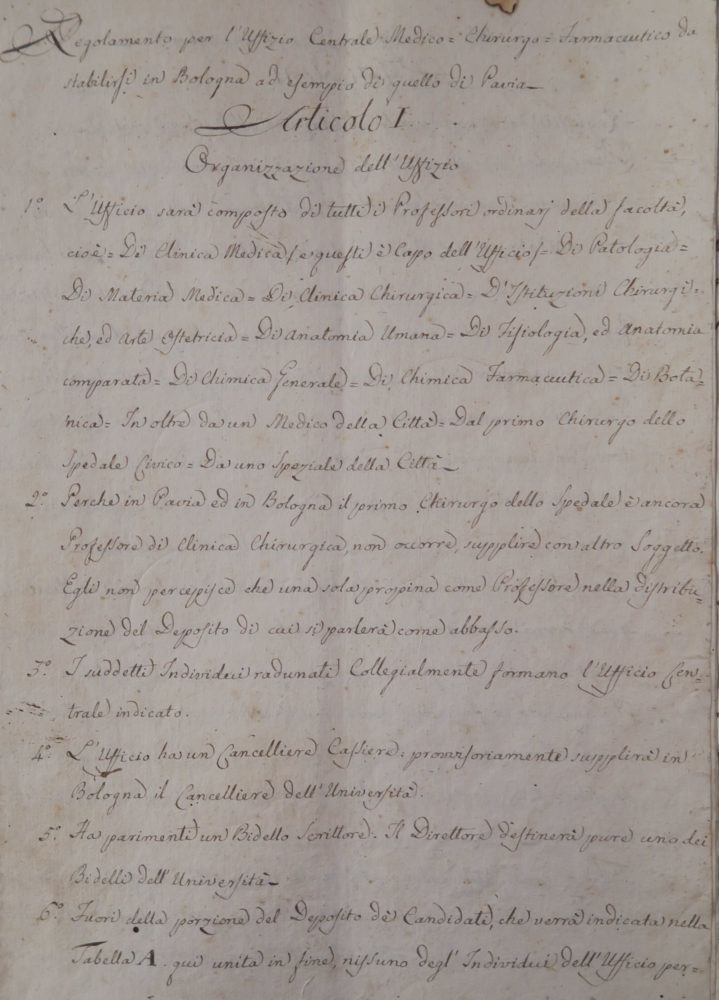

The regulations (Figure 2) of the Bologna Central Medical Office contain a detailed description of how the pharmacists’ examination was held as well as a description of the different oath formulas. The Office was composed of all the full professors of the Faculty of Medicine, the lead surgeon of the Civic Hospital as well as a physician and a pharmacist from Bologna.

Figure 2: Regulations of the Central Medical, Surgical and Pharmaceutical Office of Bologna (1805). ASB, Prefettura del Dipartimento del Reno, Atti generali, n.504.

Article 2 of the Office regulations lists the necessary requirements for aspiring pharmacists to be qualified as such. First and foremost, the first paragraph clearly specifies that “no one in the Kingdom may work in a medical branch without previously being granted the public qualification by the Central Office”. Pharmacists were required to provide a certificate of good conduct and a diploma of higher education from one of the two national universities (either Pavia or Bologna). They were also asked to complete a five-year apprenticeship at a recognized pharmacy. In the health sector, would-be pharmacists were the health professionals who had to tread the longest training path of all: physicians and surgeons were indeed required only a 2-year-apprenticeship.

Article 5 well describes the examination that aspiring pharmacists had to sit. Its title, “Exam Structure for Apothecaries”, attests to the interchangeability of the words apothecary and pharmacist at the time. Aspiring pharmacists were actually required to take two examinations: a practical and a theoretical one. The practical exam took place in a laboratory where the professor of General Chemistry, the professor of Pharmaceutical Chemistry and a licenced pharmacist asked the candidate to perform at least five chemical-pharmaceutical procedures. The theoretical exam was held in the headquarters of the Central Medical Office at the presence of all its members. The Professor of Botany, who was the first to test the candidates, assessed their knowledge on medicinal plants. Then, the Professor of Medical Sciences asked questions using the collection of drugs owned by the university. He showed aspiring pharmacists resins, gums, roots, seeds, and barks of exotic plants and tested them on these. The exam finished with questions asked by the professor of General Chemistry, the professor of Pharmaceutical Chemistry and the licenced pharmacist. Their questions revolved around laboratory activities, the general principles of chemistry and the candidate’s progress.

At the end of the examination the board secretly voted whether or not the candidate was approved. If the candidate passed the examination, they were invited to the Office Hall for the final ceremony, during which they were awarded the qualification diploma.

An accurate description of the ceremony, the proclamation speech and the oath can be found in article 7, “Methods to grant formal qualification”, and its appendices. When the candidate entered the hall, the Director of the Central Medical Office first read the following proclamation speech (12):

Having fulfilled the requirements imposed by the Medical Regulations, and having given sufficient

proof of your ability to practise Pharmacy, I declare, before this Medical Office, that you [Name Surname] have

been approved and have been granted, in accordance with the aforementioned Regulations, the

faculty to practise Pharmacy anywhere in these States for the benefit of the sick, and you will

therefore take the usual oath before this Medical Office to swear exact observance of the Laws in

force for Persons with this faculty.

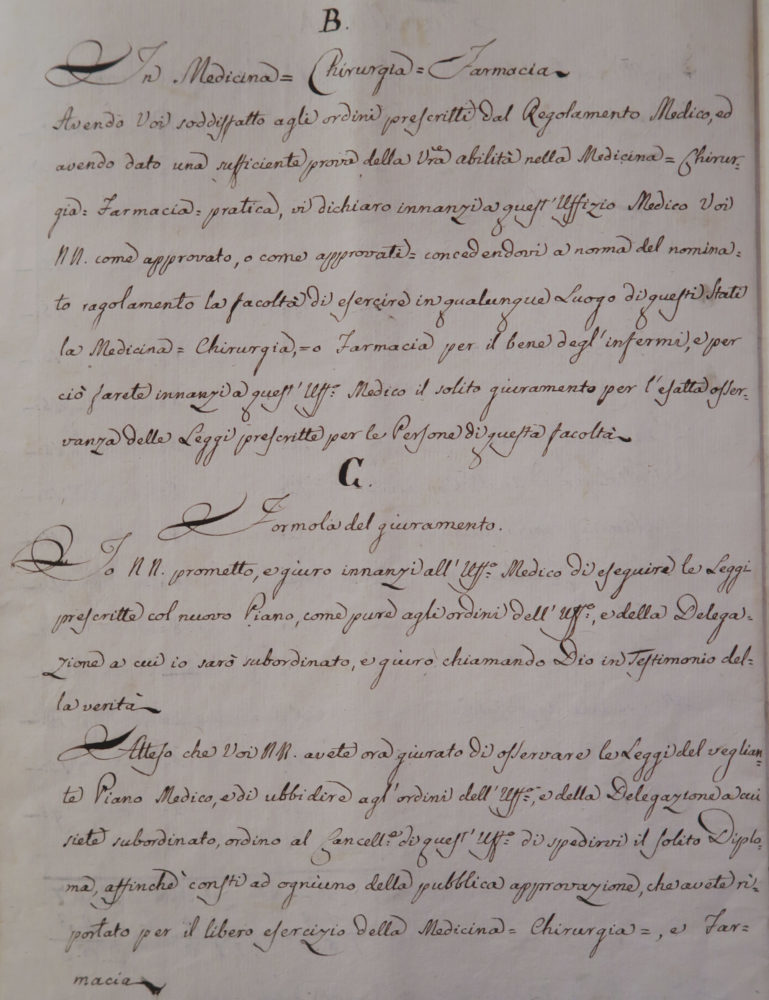

At this point, the newly approved pharmacist solemnly swore the following oath (13) before the Medical Office (Figure 3):

I, [Name Surname], promise and swear before the Medical Office to obey the Laws of the new Plan, as well as

the orders of the Office and the Delegation to which I will be subordinate, and I swear by calling

God as my witness to the truth.

Figure 3: Proclamation and oath formulas for qualifying examinations for physicians, surgeons and pharmacists, contained in the Regulations of the Bologna Central Medical, Surgical and Pharmaceutical Office (1805). ASB, Prefettura del Dipartimento del Reno, Atti generali, n.504.

As opposed to the oath made upon receiving the academic degree, the oath taken upon being granted the pharmacist qualification was very concise and was the same as the one that physicians and surgeons had to swear. Basically, pharmacists promised to obey the Central Medical Office and its delegates. As we have seen, the oath that used to be taken upon obtaining the Academic Degree was already thorough and complete enough. It is probably for this reason that legislators did not deem it necessary to draft another extensive version of the oath to be read on the occasion of the qualification.

At this point the Director responded with the following formula (14):

Since you, [Name Surname], have now sworn to observe the Laws of the vigilant Medical Plan, and to obey the

orders of the Office and the Delegation to which you are subordinate, I order the Chancellor of this

Office to send you the usual diploma, so that everyone may be aware of the public approval you

have received for the free exercise of the Pharmacy profession.

4. THE SPECIAL LICENCE TO CREATE CHEMICAL-PHARMACEUTICAL COMPOUNDS ON A LARGE SCALE

In the regulations pertaining to the examination, there is one interesting rule which is worth mentioning: those candidates who showed “extraordinary doctrine and experience” and passed the examination brilliantly, were awarded – if they so requested – a special qualification that gave them the privilege of being allowed to produce large quantities of chemical and pharmaceutical compounds and to sell them wholesale to other pharmacists (15). The introduction of this special qualification can be perceived as an early version of what would be, in the decades to come, the birth of the modern pharmaceutical industry.

In his writings (16), the Italian pharmacy historian Giulio Conci recalls that, in the 17th century, a few specialised pharmaceutical workshops in Milan and Venice used to produce chemical compounds. He also recounts that, as early as the 16th and 17th centuries, when Paracelsus’s chemical compounds were introduced into therapies, apothecary shops equipped with the necessary tools and expertise to prepare the new compounds began to open and probably started supplying those smaller apothecary shops that were unable to produce them. However, the fact that it was these regulations that created a specific licence for pharmacists to be officially allowed to produce medicines in large quantities is extremely interesting. Although it is likely that in the past this practice was already happening to a certain extent, we do not find evidence of a previously existing similar licence, at least in the regulations of the “Arte degli Speziali” (the Society of Apothecaries) and of the Bologna Medical College. On the other hand, as we have seen, the new regulations of the Bologna Central Medical Office – which was born on the example of the Pavia Central Medical Office – totally included the possibility for those most brilliant candidates to produce chemical pharmaceutical compounds on a large scale. This provided the new pharmacist with a fantastic professional and economic opportunity.

Even though a whole paragraph of the Regulations of the Central Medical Office was devoted to this special licence, this opportunity was not well regulated and the criteria by which this type of privilege could be granted were not specified.

The criteria were defined on 7 July 1806 during a meeting of the Office (17). On that occasion it was decided that only those pharmacists who were unanimously approved by all professors – or approved by all of them but one – could benefit from this opportunity.

This decision was made as a result of the pressing demands of the pharmacist Francesco Bonini, who had successfully passed his qualification exam on 24 June of that same year (18). His performance had been brilliant and he wished to be granted the permission to produce large quantities of both simple and compound medicines to be sold to other pharmacists. For this reason, he wrote two letters (19) to the Central Office asking for its official permission. Initially, the Office Chancellor sent him the official report of the meeting of 24 June during which Bonini had been granted the qualification. However, this report did not expressly state the permission to manufacture medicines in large quantities and therefore the pharmacist wrote a new letter in which he clearly stated that without the official permission he refused to “undertake such a considerable effort as the large-scale manufacturing of medicines is”. Another argument against their manufacturing without permission was linked to the “considerable expenditure that the setting up of a suitable chemical laboratory would entail”. The letters prove that granting an official licence like the one in question was something new that had never happened before. As a result of these pressing requests, the Office issued a new certificate that officially allowed to produce and sell large quantities of chemical-pharmaceutical compounds to other pharmacists.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The oath that pharmacists had to make upon obtaining their academic degree during the Napoleonic period is proof of the responsibility that the State entrusted to “a person who is a depositary of the public faith and authorized by the public magistrates to preserve the lives of their fellow”. With the oath, pharmacists promised to carefully prepare medicines, by following physician’s prescriptions to the letter and by being careful not to dispense unusual doses that could harm patients. In case it was necessary, they could also reduce a medicine to the minimum effective dose if they thought it could be dangerous for the patients’ life. They also evoked the new concepts of equality and brotherhood both in the treatment and in the preparation of medicines for the sick. At present, this represents the first academic oath ever taken by Italian pharmacists.

The documents of the Central Medical, Surgical and Pharmaceutical Office are themselves exceptional. Thanks to the Office regulations, we can learn about how the pharmacist qualification exam took place. The pharmacist second oath, the one that was made upon obtaining the qualification, was very concise and did not show any peculiarity, as it was identical to the one of physicians and surgeons. On the other hand, the documents found regarding the new licence to produce medicines on a large scale are very interesting: they are early evidence of the shift towards the mass production of medicines that the pharmacy industry underwent in the following decades.

6. REFERENCIAS

- Rosa M, Verga M. La storia moderna: 1450-1870. Milan: Ed. Bruno Mondadori 2003; pp. 136-141.

- Bollettino delle Leggi della Repubblica Italiana, from N. 1 to N. 20. Milan: Reale Stamperia 1802-1805; pp. 295-308.

- Foglio Officiale della Repubblica Italiana, from N. 1 to N. 15. Milan: Reale Stamperia 1802-1805; pp. 155-216.

- Ciuti F. Il Collegio dei fisici e l’Arte dei medici e speziali di Firenze: dalla Repubblica allo Stato mediceo (XIV-XVI secolo). Archivio Storico Italiano 2012; 631: 5-6.

- Piani di Studi e di Disciplina per le Università Nazionali del 1803. Milan: Luigi Veladini Stampatore Nazionale 1803.

- Bologna State Archive (ASB), Studio, n. 530, Disavanzamento Lauree Mediche e Chirurgiche, Gradi Farmaceutici (1803-1804).

- Federazione degli Ordini dei Farmacisti Italiani (F.O.F.I.), Giuramento del Farmacista, Testo approvato dal Consiglio Nazionale il 15.12.2005. Available at: https://www.fofi.it/pg_f.php?id=21

- According to the agreement, the Health Commission was responsible for examining Barbers, Midwives and “Gargioni” (apothecaries in the first degree), while the University was responsible for examining Physicians, Surgeons, Pharmacists and Master Apothecaries.

- ASB, Prefettura del Dipartimento del Reno, Atti generali (1803-1813), Tit. XXV (Sanità), Rub. 2, 1804, inside “Sanità Commissione, Rapporto di concerti presi col Rettore dell’Università intorno agl’esami relativi a Polizia Medica”, n. 538.

- ASB, Prefettura del Dipartimento del Reno, Atti generali (1803-1813), Tit. XXV (Sanità), Rub. 2, 1805, inside “Istruzione Pubblica – Direttore Generale: Regolamento per l’Uffizio Centrale Medico Chirurgico Farmaceutico da stabilirsi in Bologna ad esempio di quello di Pavia”, n. 18860.

- Bollettino delle Leggi della Regno d’Italia, Part III from N. 29 to N. 39. Milan: Reale Stamperia 1806; pp. 923-941.

- ASB, Prefettura del Dipartimento del Reno, Atti generali (1803-1813), Tit. XXV (Sanità), Rub. 2 ,1805, inside “Istruzione Pubblica – Direttore Generale: Regolamento per l’Uffizio Centrale Medico Chirurgico Farmaceutico da stabilirsi in Bologna ad esempio di quello di Pavia”, n.18860.

- Ibidem.

- Ibidem.

- This licence was also granted during the proclamation and was accorded in compliance with paragraph 4 of article 5 of the Regulations of the Central Medical Office.

- Conci G. Pagine di Storia della Farmacia. Milan: Vittoria Edizioni 1934; pp. 270-272.

- ASB, Prefettura del Dipartimento del Reno, Atti generali (1803-1813), Tit. XXV (Sanità), Rub. 2 ,1805, unnumbered act (Office meeting on 7 July 1806).

- Ivi, n. 23.

- Ivi, unnumbered act (Office meeting on 7 July 1806).